William Scott RA (1913-1989)

Nationality

British

Education

1928-1931: Belfast College of Art

1931-1935: Royal Academy Schools

Taught

1946-1956: Head of Painting at Corsham Court, Bath Academy of Art

Lecturer at the Royal Academy Schools

Artworks

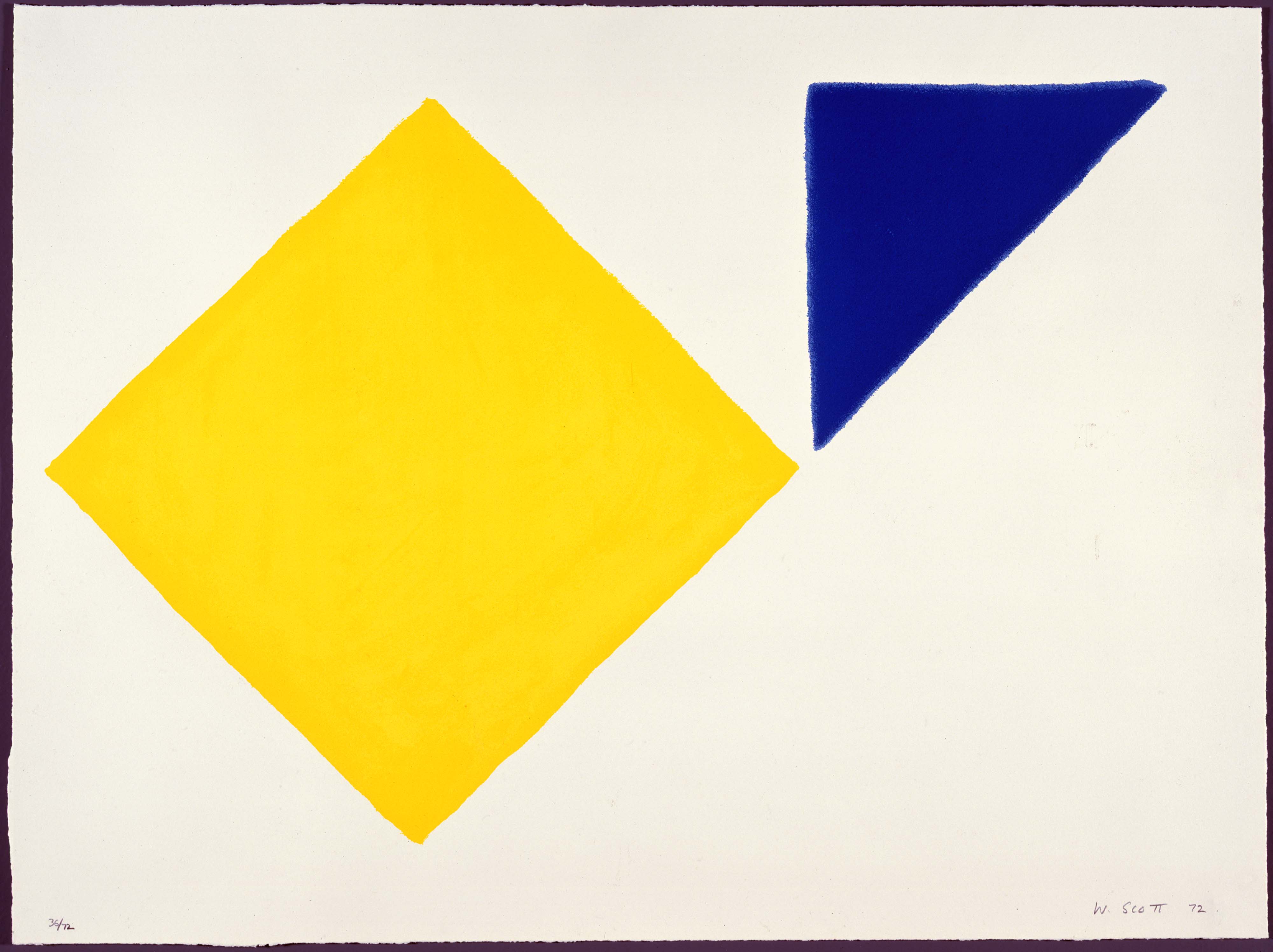

First Triangles, (1972) and Yellow Square plus Quarter Blue (1972)

Background

A painter of Irish and Scottish descent, Scott spent his childhood in Scotland and from 1924 at Enniskillen, County Fermanagh. His Irish father introduced him at the age of 14 to the work of Cézanne, Modigliani, Picasso

and Derain. He completed his studies at Belfast College of Art and the Royal Academy Schools in London. Late in life the artist suffered from Alzheimer's disease.

The artist

While Head of Painting at Corsham Court, Bath Academy of Art Scott got his practising artist friends (such as Peter Lanyon) to teach at the Academy. By 1956 his success as an artist allowed him to give up full-time teaching,

although he would remain interested in, and involved with, art school education for the rest of his life – in 1973 Scott toured India, Australia and Mexico as a British Council lecturer.

In 1958 he represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale, and won the International Critics Prize at the he 1961 São Paulo Bienal. The 1960s saw major shows around the world, and in 1963 Scott was invited by the Ford

Foundation to take up a residency in Berlin. In 1972, the Tate Gallery mounted a major retrospective, which included more than 125 paintings dating from 1938 onwards. He received honorary doctorates from the

Royal College of Art in London, Queen's University Belfast and Trinity College Dublin. In 1984 Scott was elected a Royal Academician. His son, James made the 1985 film, Every Picture Tells A Story about

the artist’s early life for Channel 4.

First Triangles; Yellow Square plus Quarter Blue

The collection includes two prints from the complete set of 16 published in 1972 by Leslie Waddington Graphics that William Scott called Poem for Alexander - Towards Euclid.

Highly intellectual in its conception the series dealt with Euclid's ten universal, mathematical ‘truths’. Although the pure geometry of the classical ideal is diluted by Scott's freehand construction, the formal elegance

of the prints is seductive and the symmetrical arrangements breathe with an agreeable movement and life.

‘Alexander’ and ‘Euclid’ evoke a geometric system reflecting the Hellenic love of beauty, worked out by one of the greatest intellects among the Greeks, in the town that Alexander founded. From ten axioms - absolutes

once felt to be self-evident - Euclid arrived by a deductive method at a set of abstract mathematical concepts - pure thought, permanent and ideal, unlike the corruptible objects of this world. As Plato reasoned,

art - being concerned with illusion - was falsity. Geometry was truth.

In Lawrence Alloway's opinion, Scott represented "irrational expression by malerish means" and was one of the abstractionists said to "melt, bury or fracture platonic geometry". Ronald Alley felt that, despite the geometric

division of his picture surface, Scott did not make geometric paintings. For Herbert Read, the painter's abstractions were "always abstractions from a phenomenal object, - directed not towards some extra-phenomenal

ideal of harmony, but towards a revelation of some vital quality . . ."

Scott's suite of sixteen images was realized with the help of Chris Prater of Kelpra Studio, one of the most celebrated screenprinters in the world. As promised in his poem, the artist began by division of imperial sheets.

Thereafter, the precise beauty of Euclid's ideal theoretical forms had to submit to the ‘controlled messiness’ of nuance, smudge and blot. Right angles, constructed without a straightedge, took on the patterns of

a rain-splashed lake. The rectangular hyperbolae from conic sections, wavered instinctively away from their trajectories. Squares were drowned, freehand, in an intensity of cobalt. Euclid's dubious parallel

lines, stretched theoretically to infinity but stopped short of necessity; Scott drew them against everchanging skies, or rising like a ladder above a grass plain, rather than a green plane. Two equilateral triangles (among

God's regular building blocks, according to Timaeus) are made to float in fields of gold or dusty brown. Balance and order, but the cerebral is caressed by the hand.

Even the printing method celebrated transience and change. The gouache models on which the printer based the screens were altered by the artist as he went along; a patch of true blue sky, became a turquoise wash; his

crisp white forms on cream drawing paper, adjusted to cream ones on the printer's purer sheet.

Not quite Euclid then, and not for Euclid's Alexander but for the artist's grandchild, Alexander Scott.