THE CNAA art collection: Victor Pasmore, Britain's art schools and higher education

A final act of the National Council of Diplomas in Art and Design (NCDAD) was to assemble an art collection intended to celebrate the history and achievements of Britain's art schools, at a cost of £10,000, in 1974. NCDAD had administered art education since 1961, but, by 1974, it was superseded by the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA).

At the point of the NCDAD’s dissolution its functions and the art collection were inherited by the CNAA. The collection has shifted locations since then, but today, under the care of the Open University, it is on show throughout Senate House.

Victor Pasmore is one of the 25 artists featured in the collection, and, through his career, it’s possible to trace the relationship between British art and design education and the higher education sector through the 20th century. He co-founded one of the few private art schools in 20th century Britain, in direct opposition to the prevailing approach to art education, and later as head of painting at Newcastle University set about planning courses described, by Stuart MacDonald in his History and Philosophy of Art Education, as “an important step in the history of art education” (MacDonald, 1970, p. 360).

Art and design became the first publicly funded form of education in the UK, with the establishment of the Government School of Design in 1837 (which became the Royal College of Art in 1896). The School was replicated throughout Great Britain and Ireland, with the express intention of supplying a workforce able to meet the growing demands of industry for better designed, and, therefore, more competitive products (Cornock, 2016).

Art and design continued to develop within an expanding publicly funded further education system, largely independent of and distinct from the university sector, but welded to a commercial design ethos. There were around 120 publicly funded independent art and design schools in the UK by the beginning of the 20th century (Bird, 2000).

Pasmore, along with two Slade graduates, William Coldstream and Claude Rogers, founded a school of Drawing and Painting, later known as the Euston Road School, in 1937: it remains one of the few examples of a 20th century private art school in the UK. Given the prevalence of publicly funded art and design schools its appearance was as much ideological as market driven. The school was established in reaction to the predominance of applied arts and industrial and commercial design throughout the public sector. It concentrated solely on drawing and painting, emphasising realism rather than abstraction, and promoting technical skills that were seen as being at risk of neglect or even repudiation (Laughton, 1986).

The Euston Road School was a serious proposition from its beginning: established Bloomsbury artists Augustus John, Vanessa Bell (sister of Virginia Wolfe), Duncan Grant and John Nash were all associated with it, and it received partial funding from both Kenneth Clarke, then the director of the National Gallery, and Samuel Courtauld, industrialist and art collector. It recorded 100 visiting students and artists during its first year, and in 1938 relocated to larger premises at 314/16 Euston Road, where it was situated above a “fun-fair”. Stephen Spender found the atmosphere compelling enough to briefly consider abandoning poetry for painting (Laughton, 1986). The school closed with the advent of the Second World War; by the War’s conclusion the staff would all relocate to the public sector. Examples of the School’s work can be found on the Tate website.

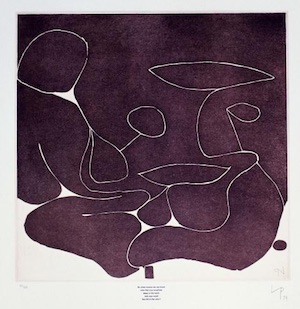

Pasmore was appointed Head of Painting in Camberwell College of Art’s painting department during the war years, after deserting the army and a spell in prison. He recruited both William Coldstream, and Claude Rogers, and two of the Euston Road School’s most promising pupils, Lawrence Gowing and B.A.R. Carter, to the teaching staff, where their ideas were further refined and disseminated. However, Victor Pasmore’s work in the CNAA collection bare little trace of the aesthetic principles espoused by the Euston School. These seven works, all Intaglio prints, forming a suite titled Correspondence, are a clear product of his conversion to abstraction in 1948 (Alley, 1998). This conversion was described by the critic Herbert Read as one of the momentous moments in the history of British post-war art (Stevens, 2008).

Victor Pasmore would go on to the Central School of Arts and Crafts, under William Johnstone, and lead one of the few BA art courses in the university sector prior to 1992, when he became Head of the Department of Painting at King's College, Durham/ Newcastle University (1954 to 1961). His tenure, along with that of Richard Hamilton – also represented in the collection - saw the introduction of elements of the “basic design movement” into British art education – or to use the phrase Pasmore endorsed “developing process” (Yeomans, 1987). A Bauhaus concept, first propagated in Britain by Johnstone at the Central School, students acquired basic principles of painting or design from direct analysis of their own experiences with materials, rather than learn a series of received ideas (Thistlewood, 1992; Yeomans, 1987). It was strongly influenced by the works of Kandinsky, Klee and Itten. “The course at Newcastle was representative of certain aspects of the basic design movement which marked a radical change in art educational thinking in the post-war period” (Yeomans, 1987, p. 2).

The basic design approach was not then, nor more recently, without criticism.

The work of Victor Pasmore, Richard Hamilton, Tom Hudson and Harry Thurbron has been criticized as pseudo-scientific, politically naïve, authoritarian, an insensitive to the commercial and industrial needs of the country.…they have been accused of breaking down previous training in art skills and techniques that a generation of visually and technically incompetent art graduates has been inflicted on English society”

(Forrest, 1985, p.147).

Victor Pasmore left higher education in 1961, the point at which the entire discipline of art and design was subject to the most through going restructuring since that of Henry Cole’s in the mid-19th century. It was the result of the National Advisory Council of Art Education’s first report (1960), led by a founding member of the Euston Road School, and then Slade professor of Fine Art, William Coldstream (NACAE, 1975). The implementation of the report’s recommendations set art and design education on a course of academic elevation and, ultimately, wholescale incorporation into the university sector. Independent art colleges disappeared as they were combined with other institutions to form polytechnics, and, in 1992, with the conversion of polytechnics to universities, the CNAA itself vanished.

References

- Alley, R. (1998, January 26). Obituary: Victor Pasmore. Retrieved 16 January 2017, from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/obituary-victor-pasmore-1141076.html

- Bird, E. (2000). Research in art and design: the first decade. Working Papers in Art and Design Journal, 1: The foundations of practice-based research. Retrieved from http://www.herts.ac.uk/research/other/art-design/research-into-practice-group/production/working-papers-in-art-and-design-journal/volume-1-research-into-practice-2000

- Cornock, S. (2016). Celebrating the achievement of the art schools: a new resource (The CNAA Collection). Senate House. Retrieved from http://cnaa.senatehouselibrary.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/Celebrating%20the%20achievements%20of%20the%20Art%20schools.pdf

- Forrest, E. (1985). Harry Thubron at Leeds, and Views on the Value of his Ideas for Art Education Today. Journal of Art & Design Education, 4(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.1985.tb00155.x

- Laughton, B. (1986). The Euston Road School: A study in Objective Painting (First Edition edition). Aldershot, England: Scolar Press.

- MacDonald, S. (1970). The History and Philosophy of Art Education. London: University of London Press.

- NACAE. (1975). First report of the National Advisory Council on Art Education: The first Coldstream report (1960). In C. Ashwin (Ed.), Art education : documents and policies, 1768-1975 (pp. 93–101). London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

- Stevens, C. (2008). Late At Tate: Victor Pasmore. Retrieved from http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/audio/late-tate-chris-stevens

- Thistlewood, D. (1992). A continuing process: the new creativity in British art education 1955-65. In D. Thistlewood (Ed.), Histories of Art and Design Education: Cole to Coldstream (pp. 152–168). Burnt Mill, Harlow, Essex, England: Longman.

- Yeomans, R. R. (1987). The foundation course of Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton, 1954-1966 (Ph.D.). Institute of Education, University of London. Retrieved from http://eprints.ioe.ac.uk/7507/

Stephen Hunt, CGHE Research Associate, UCL

Stephen Hunt, CGHE Research Associate, UCL